🍹

Purchasing power measures the value of goods that can be bought with a specific amount of a currency. Purchasing power is a relative measure that is most relevant when analyzed for changes over time. For example, if a dollar is valuable enough to buy five apples for one dollar at a point in time, and one dollar can only buy four apples a year later, then the dollar's purchasing power will have decreased over the year.Prices

Inflation is the number-one enemy of economy-wide purchasing power. Inflation is the process whereby prices slowly rise throughout all sectors in an economy, effectively reducing the purchasing power of fixed assets and current income levels. According to Investopedia, inflation is neither inherently good nor bad. It is an ever-present reality that must be counterbalanced by increases in wages, interest rates and other factors over time. In periods of deflation, in which prices drop throughout an economy, relative purchasing power theoretically increases. Deflation, however, can be caused by negative economic issues which may themselves reduce purchasing power. Economics use the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to measure purchasing power by tracking price changes for commonly purchased goods.

Wages and Employment

Employment levels and average salaries can have a tremendous effect on economy-wide purchasing power. Taken in aggregate, the more people who are employed, and the more money they earn, the more discretionary funds they will have to spend throughout the economy. Employment factors affect total purchasing power rather than causing a relative shift. Employment does not necessarily cause a currency to become stronger, yet it puts more currency in the hands of consumers, boosting commercial and tax revenues. Per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP), calculated by dividing GDP by population, is a popular measure of economy-wide income levels for consumers and businesses.

Currency Considerations

Fluctuating exchange rates affect purchasing power in relation to other currencies. As one nation's currency devalues against another, goods in the second country will be higher in the first country's currency. This fact in itself does not necessarily affect purchasing power for domestic purchases, but businesses that rely on suppliers in the second country can experience dramatic price increases for imported goods. These businesses may pass their higher costs on to consumers, contributing to inflation and diminished domestic purchasing power.

Availability of Credit

The willingness of banks to lend money to consumers and businesses affects total purchasing power in much the same way as higher salaries and employment levels. With a line of credit, consumers and companies can spend more than they actually have, giving a static, ever-present boost to their personal purchasing power. Lenders reap the benefits of credit agreements by earning interest revenue, which gives them more money to spend in the economy, boosting per capita GDP.

🌳

Income and employment theory, a body of economic analysis concerned with the relative levels of output, employment, and prices in an economy. By defining the interrelation of these macroeconomic factors, governments try to create policies that contribute to economic stability.Modern interest in income and employment theory was triggered by the severity of the Great Depression of the 1930s in the United States and Europe. In its failure to explain the persistent high levels of unemployment and the low levels of business productivity, the prevailing school of classical economics lacked solutions for the problems of that era.

John Maynard Keynes offered new thinking on income and employment theory with the publication of General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). Building on his theory, Keynesians have stressed the relationship between income, output, and expenditure. Since transactions are two-sided—in that one person’s income is another person’s expenditure—the relationship could be expressed in the form of a simple equation: Y = O = D, where Y is the national income (i.e., purchasing power), O is the value of the national output, and D is national expenditure. What this equation means is that effective demand is equal to income as well as to output. Since consumers can either spend or save their income, Y = C + S, where C is consumption and S is savings.

Similarly, on the output side, production is either sold to final customers or invested in inventory or new capital equipment, (such as production plants or machinery). So O = C + I, where C represents sales to final customers and I investment. Thus, C + S = C + I and, therefore, S = I. However, while savings and investment may thus be equated from an accounting standpoint, in fact, actual planned savings and planned investment may differ in real life. Keynesians say that economic instability stems from this discrepancy between savings and investment.

Suppose, for example, that in a given period savings rise above their previous levels. The effect will be a reduction in present demand with a prospect of increased future demand. If, by coincidence, additional capital formation (investment, such as in inventory) rises by the same amount, productive resources will continue to operate at capacity; there will be no change in the level of activity, and the economy will remain in equilibrium. However, if capital formation does not rise, then the demand for labour will fall and, assuming that wages do not fall, some workers will become unemployed and lose some of their current income.

The fall in incomes further reduces consumer demand while also reducing the rate of savings. Provided manufacturers do not alter their investment plans, equilibrium will be established at a lower level of income. In reality, then, it is not savings that are unstable but the level of investment: a fall in investment and an increase in savings will both produce a dampening effect on the economy. Conversely, a rise in investment or an increase in consumer spending will tend to stimulate the economy.

This example illustrates how changes in savings or investment will affect changes in national income, but it does not show the extent of those changes. The actual degree of change is determined by what Keynes called the “consumption function” (that is, the level of spending that is based on disposable income). Keynes’s primary aim in developing his theory was to show that, under certain conditions the economy could become stuck in a disequilibrium, with productive resources in surplus (i.e., high level of unemployment) but income and output unable to rise sufficiently to reach an equilibrium. Put simply, Keynes argued that, when business was unwilling or unable to increase investment because of low demand, additional government spending could spur new spending and eventually pull the economy out of disequilibrium. Keynesians believe that fiscal policy—such as an increase in government expenditure or a reduction in taxation—is the most effective way to offset the lack of private demand.

A competing theory of income and employment, the monetarist approach, places the quantity of money in the controlling role. The analysis of the effects of increasing or decreasing the money supply is approximately parallel to that of the consumption-and-savings relation. The rules of thumb derived from the two theories may, in fact, be combined: an excess demand for goods or an excess supply of money (the two may be seen as aspects of the same phenomenon) will be associated with rising income; similarly, an excess supply of goods or an excess demand for money will be associated with falling income. Monetarists, such as Milton Friedman, have advocated monetary policy as the proper countercyclical tool of government.

Both the Keynesian and the monetarist theories have two notable shortcomings. First, both are demand-side theories and are therefore incapable of contributing toward the long-term considerations of economic growth. Second, both assume that people can be fooled over and over again; in reality, as they learn to anticipate government policies based on the monetarist or Keynesian models, people act in ways to offset these policies and thus negate the government actions.

🍄

KONTAN.CO.ID - JAKARTA. Indeks harga saham gabungan (IHSG) selama sepekan terakhir telah terkoreksi tiga kali berturut-turut. Sebelumnya sempat menyentuh level tertinggi pada Selasa (7/11) dengan level 6.060,45. Lalu pelaku pasar memanfaatkan momentum tersebut untuk profit taking dan membuat indeks turun.

Selama bulan November, ada sejumlah saham pemberat indeks. Di antaranya, PT Bank Central Asia Tbk (BBCA) yang turun 3,84%, PT Rimo International Lestari Tbk (RIMO) turun 57,33%, PT Bank Mandiri Tbk (BMRI) turun 3,09%, PT United Tractors Tbk (UNTR) turun 7,82%, dan PT Indocement Tunggal Prakasa Tbk (INTP) turun 7,22%.

Selain itu, PT Charoen Pokphand Indonesia Tbk (CPIN) turun 5,67%, PT Adaro Energy Tbk (ADRO) turun 4,47%, PT Semen Indonesia Tbk (SMGR) turun 4,08%, PT Kapuas Prima Coal Tbk (ZINC) turun 24,28%, PT Sarana Menara Nusantara Tbk (TOWR) turun 4,29%, dan PT MNC Land Tbk (KPIG) turun 17,83%.

Riska Afriani, Kepala Riset OSO Sekuritas menyatakan, penurunan yang terjadi pada beberapa saham terbilang wajar. Misalnya seperti BBCA yang sebelumnya sudah naik beberapa kali. Sementara, tiada sentimen positif pada pekan sebelumnya, membuat pelaku pasar melakukan profit taking. "BBCA dari segi nilai dari PBV, sudah cukup mahal," kata Riska kepada KONTAN, Jumat (10/11).

Sedangkan penurunan yang terjadi pada RIMO, terbilang cukup unik. Lantaran emiten ini masih memiliki fundamental yang baik, namun justru terjadi penurunan harga yang signifikan. Menurutnya, ada tekanan yang cukup besar dari pemegang saham.

"Kinerjanya sudah cukup bagus. Kuartal III-2017 RIMO masih mampu mencatat laba Rp 118,43 miliar. Sebelumnya rugi berkali-kali, karena di sektor ritel. RIMO harusnya positif," lanjutnya.

Sementara, penurunan pada sektor semen seperti INTP dan SMGR masih sejalan dengan penjualan dan laba yang diraih. Karena kinerjanya turun, maka membuat harga saham perusahaan juga turut turun. Namun, untuk pekan depan dia menilai ada potensi rebound teknikal pada kedua saham tersebut.

Untuk pekan depan Riska merekomendasikan beberapa emiten. Diantaranya SMGR, BMRI, PWON, TLKM, INDY, KLBF, BSDE, ITMG, MAPI, BBTN, BBCA. Beberapa emiten tersebut, juga termasuk dalam saham pemberat indeks. Yakni BBCA, SMGR, dan BMRI.

"Rekomendasi buy saham BBCA, SMGR, dan BMRI. Masing-masing target harga terdekat ada potensi ke 21.250, 10.500, dan 7.225," ujarnya.

🌳

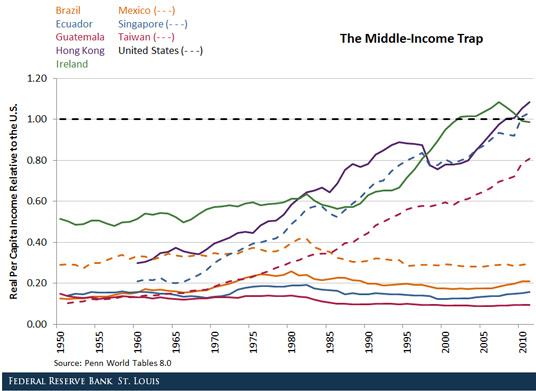

Can Countries Escape the Low- or Middle-Income Trap?

Monday, February 2, 2015

By Yi Wen, Assistant Vice President and Economist, and Maria A. Arias, Research Associate

Since 1960, economic growth in the developing world has lifted many low-income economies from poverty to a middle-income level and other economies to even higher levels of income. However, only a few countries have been able to catch up with the high per capita income levels of the developed world and stay there. By American living standards (as representative of the developed world), most developing countries since 1960 have remained or been “trapped” at a constant low-income level relative to the U.S.

This “low- or middle-income trap” phenomenon raises concern about the validity of the neoclassical growth theory, which predicts global economic convergence. Specifically, the Solow growth model suggests that income levels in poor economies will grow relatively faster than developed nations and eventually converge or catch up to these economies through capital accumulation, assuming that all countries have the same access (due to spillover effects) to the world frontier of new technologies. But, with just a few exceptions, that is not happening.

Measuring the Traps

Up to now, the growing literature about the low-income trap and the middle-income trap has focused on income divergence between the developed and developing worlds, but ignored the more pervasive phenomenon of the lack of convergence. This perspective can be important because even the poorest economies continue to grow at some positive rate every year.

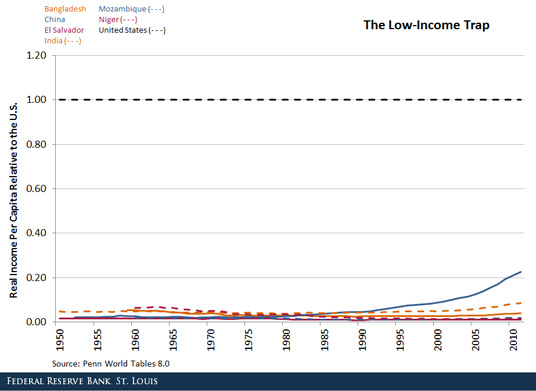

Redefining the low- and middle-income traps as situations where income levels relative to the U.S. remain constantly low and without a sign of convergence allows us to study the issue of economic convergence (or the lack of it) directly. The figures below highlight our new concept of the middle-income trap and the low-income trap. Several examples of countries that have escaped the middle-income trap to reach a high-income level and countries that have escaped the low-income trap are depicted along with those trapped countries with constant income levels relative to the U.S.

The figure above shows the rapid and persistent relative income growth (convergence) seen in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and Ireland beginning in the late 1960s all through the early 2000s to catch up or converge to the higher level of per capita income in the U.S.

Convergence implies that income growth in these economies was significantly faster than in the U.S. In sharp contrast, per capita income relative to the U.S. remained constant and stagnant at 10 percent to 30 percent of U.S. income in the group of Latin American countries, which remained stuck in the middle-income trap and showed no sign of convergence to higher income levels, despite experiencing moderate absolute growth during the same period.

The lack of convergence is even more striking among low-income countries. Countries such as Bangladesh, El Salvador, Mozambique and Niger are stuck in a poverty trap, where their relative per capita income is constant and stagnant at or below 5 percent of the U.S. level. Even though their economies might have grown moderately in absolute terms, they have not grown at a rate faster than the U.S. growth rate; thus, their relative income levels have not increased.

China has been able to grow relatively faster than the U.S. since about the early 1980s, breaking away from the low-income trap and reaching middle per capita income levels. India has also shown signs of escaping the low-income trap since the early 1990s. However, both countries still have a long way to go to catch up and converge to the levels seen in developed economies, and both have to cross (overcome) the middle-income trap on their way toward ultimate prosperity.

Why do some countries remain stagnant in relative income levels while some others are able to continue growing faster than the frontier nations to achieve convergence? Is it caused by institutions, geographic locations or smart industrial policies? Examining the phenomenon of low- and middle-income traps based on relative income will help shed new light on the study of the prevalent factors behind economic convergence (or lack thereof).

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Where Is the “Peril” of Deflation Striking Back?

- On the Economy: How Have Households Deleveraged Since the Great Recession?

- On the Economy: Oil Prices: Is Supply or Demand behind the Slump?

Comments

Post a Comment